The Franco-Algerian crisis: Troubled Waters, Windfall for Fishermen?

INSIGHT. The standoff between Paris and Algiers jeopardises economic ties between the two countries, bringing new competitors onto the scene: Italy and... Spain?

- France and Algeria have been involved in a diplomatic dispute for almost a year, following Macron's support for Moroccan sovereignty over Western Sahara, as well as subsequent events such as the imprisonment of a Franco-Algerian writer, and Algeria's refusal to repatriate its citizens. Although diplomatic relations have not been formally interrupted, economic exchanges have been severely affected, and the crisis does not appear to be over in the short term.

- Italy has taken advantage of this and the previous crisis with Spain to strengthen its relations with Algiers. In line with its Mattei Plan for repositioning itself in Africa, Italy is promoting gas pipeline diplomacy through initiatives such as TransMed, Galsi and the SoutH2 corridor. The aim is to present Italy as an energy hub in Europe while also gaining an ally in its policy of outsourcing migration.

- Spain overcame its crisis with Algeria last November. Despite the emergence of new competitors during its long absence, Spain can leverage Algeria's need for economic diversification to restore its previous trade volume. It can do so by leveraging its international position on the Palestinian issue and avoiding new controversies on regional issues.

The Paris-Algiers clash

France and Algeria have been embroiled in a diplomatic confrontation for several months, which is more than just another episode in their turbulent relationship since Algerian independence. In July 2024, President Emmanuel Macron expressed his support for Morocco's proposed autonomy plan for Western Sahara, describing it as the 'only possible solution' to the dispute. He stated categorically that 'the present and future of Western Sahara fall within the framework of Moroccan sovereignty', reaffirmed during his visit to Rabat in October.

Video by elysee.fr

This statement provoked a furious reaction from the Algerian government, which was already in the midst of a confrontation with the Spanish executive over similar support — albeit in much less forceful terms and without recognising sovereignty. Unsurprisingly, Algiers remains the primary supporter of the Polisario Front's claims, hosting over 175,000 Sahrawis in the Tindouf camps and firmly defending their right to self-determination in international forums. Algeria expressed its anger by withdrawing its ambassador to Paris, who has not yet been reinstated, although it did not adopt the same economic reprisals as with Spain.

While French support for the Moroccan position is the main cause of the dispute, there have since been a number of clashes of varying severity that have exacerbated the disagreement. Firstly, in November, the Franco-Algerian writer Boualem Sansal was imprisoned in Algiers and sentenced to five years in prison for ‘attacking the integrity of the territory’, due to his comments in a far-right French media outlet. In these comments, he claimed that Morocco had been deprived of part of its territory in favour of Algeria during decolonisation. Despite intense pressure from the French political establishment and calls for his release by the European Parliament, the writer remains in prison with no prospect of change. After Abdelmajid Tebboune was re-elected as Algerian president, a request was made for him to grant a pardon, but this has not yet been granted.

The apparent refusal of the Algerian authorities to accept their deported nationals has been a source of confrontation, particularly following the attack in Mulhouse (France) in February, which resulted in one death and seven injuries. The perpetrator was an Algerian subject to an expulsion order from French territory who had returned to France after being rejected by Algiers on ten occasions. The French Minister of the Interior has even threatened Air Algérie with sanctions for its lack of cooperation with expulsion orders.

Contributing to this climate of mutual recriminations was the arrest in January of several Algerian influencers (five men and one woman) residing in France on charges of inciting violence against opponents of the Algiers regime. The Algerian state media are also raising colonial grievances, accusing France of failing to clean up territories affected by nuclear testing and invoking the memory of the Sétif massacre perpetrated by the metropolis in 1945. The latest cause of tension was French Culture Minister Rachida Dati's visit to Western Sahara, which Algiers described as an 'extremely serious' provocation.

Although no formal economic reprisals have been taken, trade between the two countries has slowed down informally. There appears to have been a significant reduction in French wheat imports, as well as a 20% decrease in the sales of French products in general during the first quarter of 2025. In March, Volvo Trucks and Renault Trucks received an unfavourable notification regarding the resumption of activity in Algeria. However, in April, there were business-level contacts, including a visit by the CEO of the shipping company CMA CGM to Algiers, where he was received by Tebboune, and a visit by representatives of the Algerian employers' association CREA to Paris.

So, how far could the confrontation go at this point? Several analysts consider this to be one of the most serious clashes since 1962. It should be noted that the two countries have a very complex relationship, given the close ties between their societies. This means that issues of domestic and foreign policy are confused and dealt with in an emotional manner by the media and the political class, especially the French far right. Although there were some signs of reconciliation in March, including calls for calm from both presidents and a visit to Algiers by the French Foreign Minister in April, the subsequent deterioration of the situation, culminating in the mutual expulsion of twelve consular agents, suggests that a return to normality will be neither quick nor easy. This is particularly pertinent given that Tebboune has just been re-elected in controversial elections with little opposition and low turnout, and the Algerian government intends to counter international support for Morocco's position on the Sahara. Meanwhile, Macron is treading carefully with an unstable, multi-party government (he has to “cohabit” with a conservative interior minister) and is seeking to counter pressure from the far right with an eye on the 2027 presidential elections.

Italy enters the scene

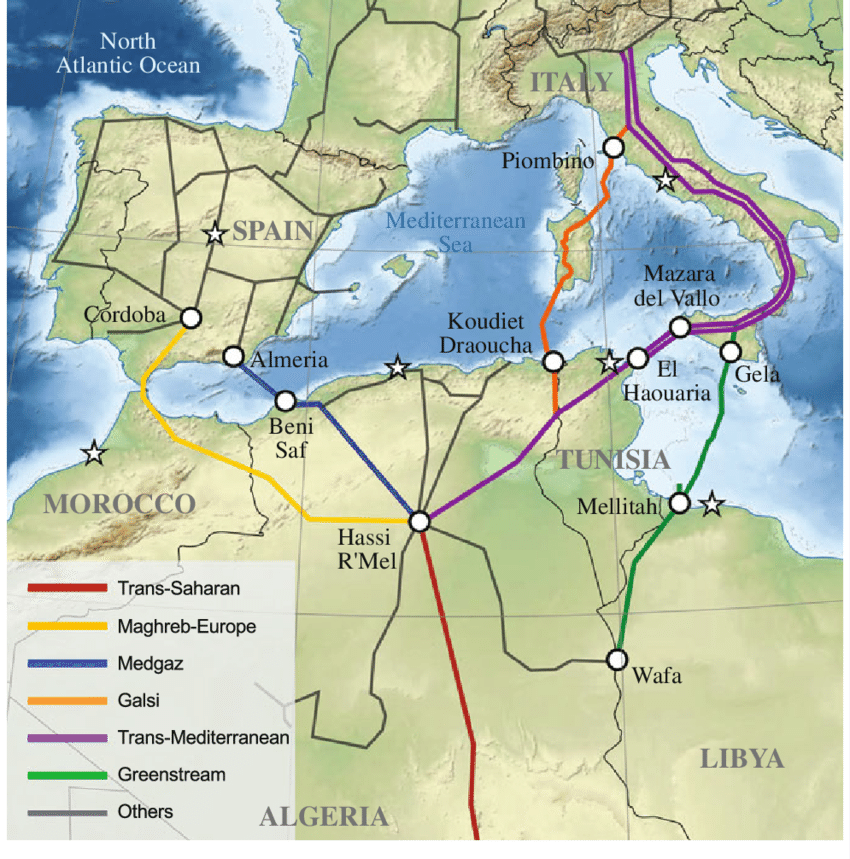

It seems that Rome intends to take advantage of the confrontation. During the recent serious crisis between Spain and Algeria, Italy positioned itself as an alternative partner to Algeria and increased its trade, thereby harming Spanish exports. Unsurprisingly, Algiers guaranteed gas supply, but threatened to prioritise Italy as its main partner in future. Indeed, the ENI-Sonatrach agreement of May 2022 (under the Draghi government) increased the volume passing through the Transmed gas pipeline from 22 to 31 billion cubic metres, with the aim of diversifying the Russian supply. Since then, Italy has sought to position itself as the European intermediary for Algerian gas, multiplying its contacts in this regard. It has even revived the “Galsi” gas pipeline project, which would link the two countries via Sardinia. This project had been shelved for over twenty years due to its high cost, but has now been revived.

The relationship between the two countries is also important for decarbonisation and the energy transition on both sides of the Mediterranean. Together with Austria, Tunisia and Germany, the two countries are participating in the “SoutH2 Corridor” project, which aims to transport green hydrogen through the Transmed pipeline and a new conduction connecting northern Italy with Central European countries. Algeria aims to generate 10% of Europe's green hydrogen and become a major supplier. This corridor would compete directly with the H2Med pipeline, a project promoted by Spain's Enagás which seeks to turn the Iberian Peninsula into a hub for this energy source. However, France has halted it due to doubts about its profitability and compatibility with pink hydrogen (obtained through nuclear energy).

Algeria has also been included in the significant Mattei Plan (named after the founder of ENI, a supporter of the Algerian Revolution), through which Italy aims to rebuild its relationship with Africa. With a budget of more than €5.5 billion, this strategy identifies several African partner countries and projects in six priority sectors: education, agriculture, health, energy, water and physical and digital infrastructure. Algeria has been selected to implement two projects focusing on agriculture and vocational training. While energy is not yet mentioned, the plan aims to be 'a bridge for energy relations between the Maghreb and Europe'. The plan has so far gained the support of the EU, which considers it compatible with Brussels' 'Global Gateway' programme, designed to encourage infrastructure investment in developing countries. Unsurprisingly, Meloni and Von der Leyen are set to chair a summit in Rome to strengthen alliances with African countries based on these cooperation programmes.

The truth is that Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni and Algerian President Tebboune have a good rapport, which is proving useful for both parties, albeit deemed as 'genuine realpolitik'. Italy gains an important partner on migration and energy — two key issues for the Italian coalition government — and calls into question President Macron, with whom she initially had a tense relationship. Meanwhile, Algiers maintains an important partner within the EU, thereby improving its position on the international stage — Meloni even invited Tebboune to last year's G7 meeting in Italy — as well as domestically, given the long-standing connection between the two societies. In fact, last March, Foreign Minister Antonio Tajani visited Algiers and boasted that relations between the two countries 'are very strong'.

Consequently, Italy has become the leading customer for Algerian exports (worth $15 billion, accounting for 29% of the total), and the third largest supplier to the North African country (just behind France), mainly exporting vehicles, machinery, and petroleum products. In 2023, Italy's foreign direct investment in Algeria reached €8.53 billion (behind the US and ahead of France), particularly in the energy, automotive, construction, agribusiness, biomedicine and digital sectors, with around 200 Italian companies being present in Algeria.

Conclusion: What about Spain?

The Iberian country suffered severely from the economic reprisals taken by Algeria in response to the shift in position on Western Sahara by the Pedro Sánchez government in March 2022. Support for the Moroccan plan, coupled with Algeria's subsequent interruption of trade with Spain (excluding gas), had catastrophic consequences for many companies, particularly in the ceramics, agri-food, and construction sectors. This was due to the freezing of projects and a sharp drop in exports to Algeria. In 2021, Spain was Algeria's third largest supplier, worth €2.19 billion. However, at the height of the crisis, exports plummeted to €356 million, rising slightly last year to €662 million (OEC data). Despite the apparent restoration of normality since November last year, Spanish businesses will undoubtedly feel the impact of competitors (China, Brasil, Turkiye) entering the market during their absence of more than two years.

Politically, relations seem to have returned to their pre-diplomatic crisis state following Algiers' appointment of a new ambassador to Madrid and the lifting of the order suspending trade. Bilateral meetings between ministers of the interior (in Madrid) and foreign affairs (within the framework of the G20 in South Africa) in February of this year are a positive sign of recovery.

It therefore seems an ideal time to revive economic activity too. The Algerian press agrees: in March, the state news agency APS reported an apparent 'improvement in the business climate' in connection with a meeting organised by the Algerian Investment Promotion Agency in Barcelona to promote investment from Spain, and other media outlets are optimistic about the full recovery of pre-crisis relations. Indeed, the process of opening up is already underway: in February, Sonatrach's management welcomed Técnicas Reunidas' CEO, and in April, Naturgy's CEO (owned by the Algerian conglomerate) Francisco Reynés.

Algeria needs alliances, both political and economic, in order to diversify its economy in the current geopolitical context. Spain has a significant advantage thanks to its expertise in renewable energy (although it faces strong competition from China, the sector's true leader and Algeria's close partner), as well as its experience in agriculture. It is also well-placed to stimulate sectors in which previous trade has already taken place, with a wide range of exports (including chemicals, metals, machinery, paper, soya, etc.). Unsurprisingly, the president of the Spanish-Algerian Trade Circle praised Spain's experience and its ‘exemplary’ economic transformation following the 2008 crisis.

Ultimately, maintaining good relations will depend on Spain avoiding taking a position on issues that are sensitive for Algeria, such as the imprisonment of Boualem Sansal, and other aspects of domestic policy. Regarding Western Sahara, Morocco is likely to continue pushing the boundaries in international forums in the coming months, having secured the support of three of the five Security Council members. Indeed, the current international dynamic seems to favour Rabat, which continues to gain support, a development that does not please Algiers, already annoyed by the Israeli presence in its neighbourhood. In this regard, Spain could leverage its stance on the Palestinian issue and its absence of a colonial past in Algeria to foster stronger historical and friendly ties, thereby promoting the shared prosperity that has been the cornerstone of its regional policy for three decades.